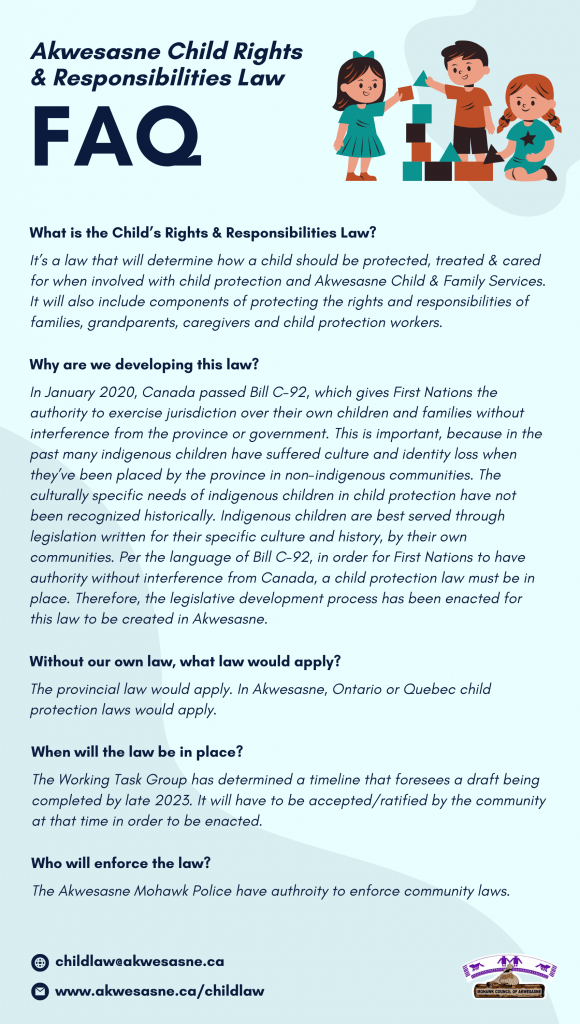

Akwesasne Child’s Rights & Responsibilities Law

The subject of developing an Akwesasne child welfare law was identified as a need during community consultation for other Akwesasne Laws (e.g. Iatathróna Raotiientáhtsera [Couples Property] Law). Specifically, this law would focus on the need to provide protection for youth in the community following one set of rules. The development of the child welfare law was identified as a priority by the community as part of the Public Comment Session in October 2018. The Akwesasne Legislative Commission did select the development of the Akwesasne Child’s Rights and Responsibilities Law as a priority in 2019.

The timing of the law is based in part on the passing of the federal Bill C-92 in Canada, which gives First Nations the right to exercise jurisdiction over their own child welfare matters provided the First Nation has a child protection law in place. Bill C-92 dictates that the First Nations law will then supersede any provincial authority. MCA had already maintained jurisdiction over our child’s rights through Akwesasne Child & Family Services, but had not yet developed a law.

The intent of Bill C-92 is to address the longstanding issue of indigenous children being over-represented in the child welfare system while being under-protected and often stripped of their cultural identity. Issues such as the devastating destruction caused by residential school placement, or the damaging results of placing indigenous children in homes of a different culture are the areas that Bill C-92 is intended to address.

MCA’s Child’s Rights & Responsibilities Law will encompass many areas of child protection with the intent to create a culturally-relevant law that is specific to the needs of Akwesasne children and families. It will be a law that serves our children and celebrates our ability to determine what is best for them, without interference from outside agencies.

This law is currently in Phase I – Law Development of the Akwesasne Legislative Enactment Regulation. See the January 2023 update below for the most recent information on the law’s development.

In the list of Frequently Asked Questions above it is mentioned that without our own law, provincial legislation would take precedence. So why not use Ontario and/or Quebec’s child protection laws?

Because Ontario and Quebec have systemic oppressive and intrusive regulations for child protection.

In Ontario:

- In Ontario, the population of First Nations people is 4.1%.

- First Nations made up 30% of the children in foster care.

There is something wrong with this statistic: Indigenous children are more likely to be in foster care. This “over-representation” is true for almost all areas of child welfare decision-making. This fact shows discrimination and racism toward First Nations in the area of child protection.

Historically, Canada’s assimilation practices are “systemic” (part of the system):

- Residential schools

- Sixties Scoop

- Loss of language

- Loss of culture

This systemic practice is a form of cultural genocide against Indigenous families and communities. This practice led to multiple negative, social and economic factors:

- low levels of education

- high levels of unemployment

- extreme levels of poverty

- inadequate housing

- health disparities

As a result, several studies from the Canadian child welfare data found ‘neglect’ as the main reason Indigenous children enter the child welfare system. Neglect is associated with household and caregiver factors that stem from chronic family concerns such as poverty, poor and unsafe housing, substance abuse, mental health issues, and social isolation. ‘Neglect’ only is six times higher for First Nations children than that of non-Aboriginal (First Nations) Children.

DISCRIMINATORY PRACTICES

In 2016, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) found that the federal government discriminated against First Nations children on reserve. The CHRT stated the federal government had discriminatory practices by not providing adequate funding for prevention services but gave incentives to agencies by placing First Nation children into care. The higher caseload for the Child Welfare agencies, the more likely the children were placed in care.

The issue has been attributed, in part, to unequal access to available resources for housing, water, and sanitation programs.

Some studies found that Indigenous children were more likely to be transferred to ongoing child protection services and placed in care (as compared to White or non-indigenous children.

TRUTH & RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC)

The TRC has urged all levels of government to:

- monitor and assess neglect investigations;

- provide Indigenous communities with adequate resources to keep families together;

- keep Indigenous children in culturally appropriate environments;

- ensure Children’s Aid Society workers receive training about the history and impacts of residential schools.

The Ontario Human Rights Commission urges the Ontario government to fully implement the TRC’s Calls to Action.

In Quebec:

- The Public Inquiry Commission on Relations between Indigenous Peoples and Certain Public Services in Québec concluded that its investigation ‘established the systemic character of discrimination’ in services.

- The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls dedicated a volume of its report to Quebec, given the province’s distinctive political, socio-historical, linguistic, religious, cultural and institutional context.

- Indigenous parents experience very negative child welfare experiences in Quebec.

CAN FIRST NATIONS HAVE THEIR OWN LAW?

The Youth Protection Act has, since 2001, contemplated an agreement between the governments (Canada/Quebec/Ontario) and an Indigenous community will establish and run their own child-welfare programs.

The first such agreement was concluded in 2018 with the Atikamekw nation.

Such programs must respect the legislation’s ‘general principles’ (Youth Protection Act).

An agreement must center on a need for ‘distinct systems, conceived in response to Indigenous realities’ and not ‘Indigenous organizations or personnel applying non-Indigenous laws and regimes.’

It’s time for a change:

An Akwesasne child protection law designed by Akwesasronon for the future of our children and seven generations yet unborn.

NEWS

- AKWESASNE CHILD RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES LAW UPDATE OHKWE’TA:KE (September 2024)

- AKWESASNE CHILD RIGHT’S & RESPONSIBILITIES LAW UPDATE (January 23, 2023)

- MCA DEVELOPING LAW FOR CHILD RIGHTS AND PROTECTION (September 23, 2022)

- CHILD’S RIGHTS & RESPONSIBILITIES LAW COMMUNITY INPUT SESSIONS (July 20, 2022)

- OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE ON LEGISLATIVE DEVELOPMENT UPDATE (July 18, 2022)

LINKS

- Akwesasne Law Enactment Regulation Summary

- FAQs for Draft Akwesasne Child Law

- Bill C-92 Summary

- Why Not Use Ontario & Quebec Child Protection Laws?